The first trailer for the Netflix series Locke & Key has dropped, and everyone is making excited noises. I read the comics a few years ago and still own the six trades, so this seemed like a good time for a reread, especially since my memory of the story has faded. I do know that the trailer seems rather different from what I remember, but I may be remembering wrong. At any rate, this is a story that revolves around magic keys, and I am a sucker for magic keys, so there you go.

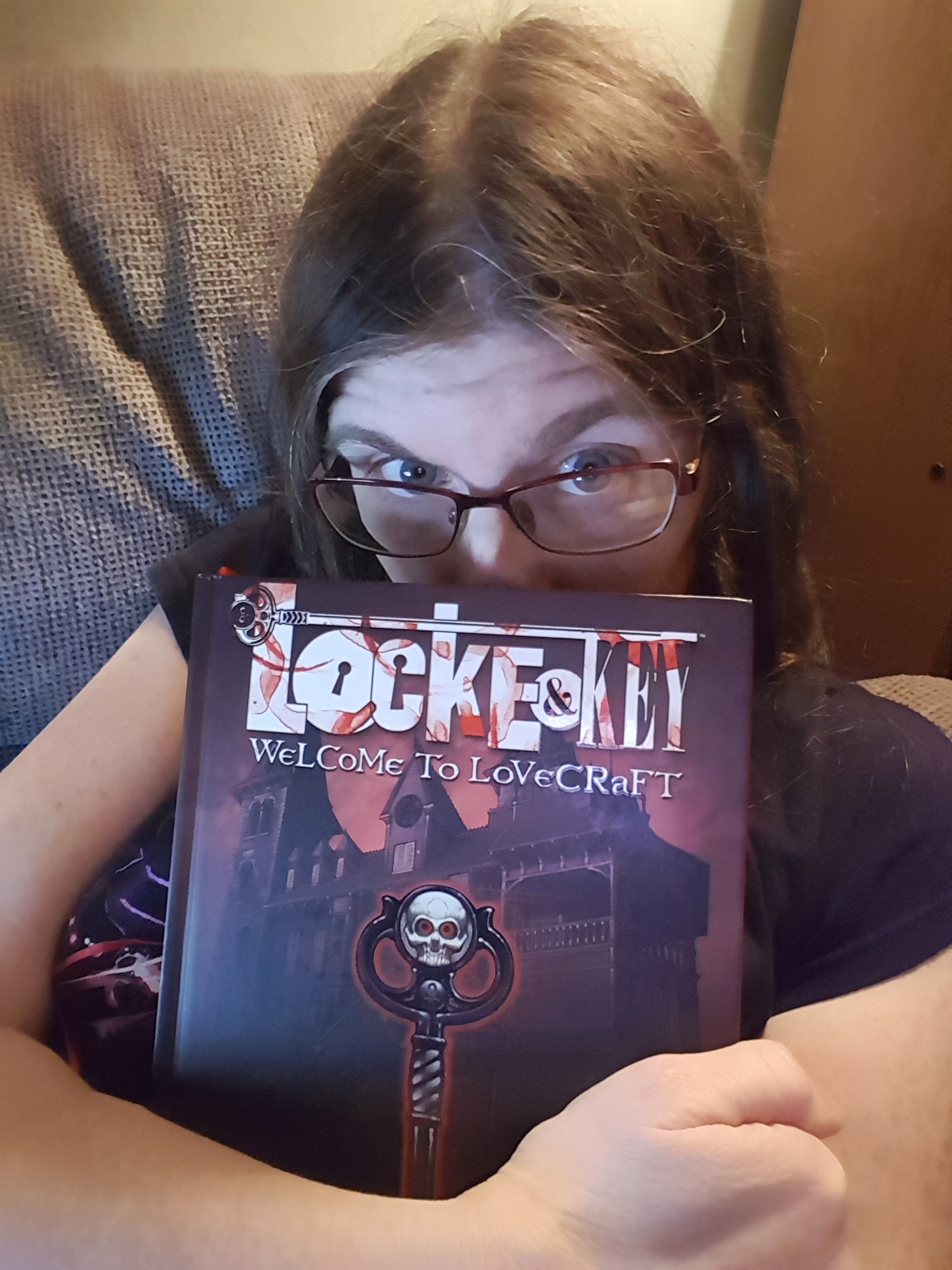

Locke & Key is a comic series by Joe Hill (story) and Gabriel Rodriguez (art), published by IDW. I’m going to devote one post to each trade volume, starting with Volume 1, Welcome to Lovecraft. I reread it in the middle of the night, when I should have been sleeping. Considering the genre, I’m probably off to a good start.

Oh…and there will be spoilers. If you’re waiting for the show and/or just haven’t picked up the books yet, stop reading now. I’m definitely going to discuss things that happen in the book.

Right. Let’s get to it:

So the first thing to know about Locke & Key is that Welcome to Lovecraft‘s extremely Gothic cover art is not an accident. The fact that the town the protagonists move to is called Lovecraft is just the tip of the extremely Gothic iceberg. The cover art is all, “You want Gothic imagery? I shall do you a big old haunted mansion with a glowing skull key in front of it,” and hey, fair enough. The story very much leans into its Gothic roots, both in its setting and in its concentration on a family history full of secrets. The family at the centre of the story is primed and ready for a descent into the Gothic. In the first few pages of the first issue, the patriarch of the family, high-school guidance counselor Rendell Locke, is murdered by Sam Lesser, one of the students he’s tried to help. The effect on his wife Nina and their three children, Tyler, Kinsey, and Bode, reverberates through the volume as the four of them, with the help of Rendell’s brother Duncan, struggle to pull their shattered lives back together. It’s a bit too bad they do it in the obviously eldritch hereditary family house in which Duncan lives.

In this first volume, which covers the family’s move to the aptly named “Keyhouse” in which Duncan and Rendell grew up, the story sticks mainly to four perspectives: Tyler, Kinsey, Bode, and Sam, the latter of whom has been locked up in juvie, though he doesn’t stay there for long. Each of the kids brings something different to the story. Tyler, who seems sixteen or seventeen, is at that awkward stage where he’s grown-up shaped but intensely insecure inside. He’s moody and seething with helpless anger, always wanting to be somewhere–and someone–he’s not. He clings obsessively to the fact that one day at school, when he was upset with his father, he told Sam he was welcome to kill Rendell. Rodriguez draws Tyler as burly and hunched over, always scowling, never comfortable. He doesn’t come across as a stereotypical petulant teen because there’s real pain behind his angsting. One of the most powerful visual techniques used to portray Tyler is his habit of looking at his reflection and seeing either what he wants to see (for instance, himself having fun) or, after his father’s murder, what he doesn’t want to see (him, effectively, as Sam, holding the gun that killed his father).

Fifteen-year-old Kinsey does her fair share of angsting, but where Tyler’s anguish comes out through his physicality, Kinsey’s makes her shrink into herself. She resolves to fly under the radar and initially shies away from making friends at her new school because she can’t stand the thought of having to talk about herself. As Tyler fixates on his perceived responsibility for his father’s death, Kinsey fixates on her perceived cowardice. When she and her siblings ran across Sam in the middle of killing their father, she grabbed her younger brother and hid instead of trying to help. Though her reaction was the right one, she doesn’t think of it that way. Like Tyler, Kinsey is continually drawn to her own reflection, but while Tyler sees alternate versions of himself, Kinsey sees herself as she is and is, every time, startled by what she regards as the stranger in the mirror. She copes by frequently altering her hairstyle, reinventing herself over and over without truly being able to change.

Bode, who is probably seven or eight, is the baby of the family and the one Locke child who isn’t sunk in self-loathing. Tellingly, when Bode looks at his own reflection, he sees only Bode; he is not estranged from himself in the way his siblings are. He provides a bit of humour in an otherwise fairly dark story, but he also acts as a point of identification, as he is as eager as the reader to get the story moving. His natural curiosity and tendency to explore kick off the plot as he almost immediately discovers the key to the house’s mostly unused front door. When he unlocks the door and steps outside, he dies and becomes a ghost. Death, in this case, is temporary; ghost-Bode simply has to return through the door in order to wake up in his body. After his initial alarm, he takes to becoming a ghost frequently and exploring the house in that form. He also makes friends with a mysterious supernatural woman who is magically trapped in an abandoned wellhouse and seems to have motives of her own. We later learn that her name is Dodge.

The odd-one-out perspective belongs to Sam, who is also in contact with Dodge and who was prompted by her to approach Rendell in search of what she calls the “anywhere key.” Hill gives Sam a sympathetic backstory, as Sam has grown up with abusive parents and feels abandoned by Rendell’s refusal to help him escape by writing him a letter of reference. Rodriguez draws him as weedy and awkward, a contrast to Tyler’s bulk. As he murders his way across America, any reader sympathy disappears, and his eventual appearance at the Keyhouse is tinged with pure horror.

The fact that Hill and Rodriguez focus on the kids highlights one of the properties of the house: adults don’t notice and can’t use the keys. Though Rendell and Duncan once explored the house in the same way Bode is doing now, they have forgotten this, which lends further tension to the scenes in which Sam demands the anywhere key from adults who (at least apparently) don’t really understand what he means. Hill draws on a common fantasy trope–the kids get to have the adventures while the adults remain clueless–and gives it a twist. This particular coming-of-age journey seems more likely to damage these already damaged young people than it does to usher them into adulthood. The magic keys are hinted to unlock doors that should really stay shut.

By the end of the volume, Sam has gone through the front door and ended up a ghost, while Dodge has been freed and has returned to her original form as a teenage boy (one of the keys, it seems, initiates a gender swap). We’ve received hints that Dodge–now calling himself Zach–was imprisoned a generation ago and that Kinsey’s running coach knows who he really is, but the mystery has only begun to unravel. It’s actually a little hard to talk about this first volume without simply summarising the plot, as the whole thing is setup. However, by the end of the book, the rules of the world are established, and the next stage of the story is poised to begin as Bode, the character most open to the potential of the Keyhouse, finds another key. Volume 2 will, presumably, continue along the path started here.

Over all, Welcome to Lovecraft sets up an intriguing puzzle box of a world whose keys offer an almost unlimited story potential. Hill and Rodriguez are giving us a slightly odd story that combines the coming-of-age magical adventure with the Gothic idea of the family with dark secrets that come out through the decaying home that symbolises the family itself. The potential of this combination will be fulfilled in later volumes.

Next up: Volume 2: Head Games.