Moving from the wide-open spaces of A Wizard of Earthsea into the claustrophic confines of The Tombs of Atuan is a bit like being buried alive, metaphorically speaking. Ursula K. Le Guin’s second Earthsea book makes a distinct contrast to her first. If A Wizard of Earthsea is all about dark mirror images, The Tombs of Atuan its its dark mirror image. The former follows a young man who journeys towards self-realisation. The latter follows a young woman who is trapped by others’ definitions of her.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the book is the fact that not very much happens in it. Le Guin slow-plays the plot, giving us several chapters of atmosphere before Ged turns up to set things moving. As I observed in one of my reaction posts, these early chapters would likely not fly with readers today. Here, however, they’re necessary. They reveal the why of Tenar’s behaviour once she has some real choices to make. In the early chapters, her life is defined by its lack of choice. She has been chosen for her role. Even her name has been taken away from her. When she seems to make a choice, which she does when she and a friend disobey the temple rules, only the friend is punished; Tenar’s personal decisions make no difference in her own life. As she grows up, she gains more power, but as Le Guin points out in her afterword, this is power over, not power to. The power over is dictated by rules and rituals, and it doesn’t truly involve choice. Tenar is haunted throughout most of the book by her execution of three prisoners: an execution she is expected to carry out, no matter what her personal feelings on the matter. She has power over the prisoners, but she doesn’t have power to do anything other than execute them.

Le Guin mentions in the afterword that in 1969, while she was writing this novel, the idea of an adventurous female fantasy protagonist was, even for her, beyond imagination. In Tenar, she gives us something more subtle. Tenar isn’t adventurous. At the end of the story, when she is finally freed, her impulse is not to explore the world but to retire to a remote part of it as a punishment for her actions. It may be tempting to see her as annoyingly passive, but in truth, she’s more paralysed than passive, imprisoned by her own belief that she is a position, not a person. Tenar undergoes at least the first half of the classic heroine’s journey. Enclosed in a space that constricts her choices and physical movement, she must find a way to be rescued.

Once Ged turns up, the story’s main conflict becomes clear. Ged, as in A Wizard of Earthsea, is all about action and movement and decision making. Tenar is dissatisfied with his magic because so much of it is illusion, but Ged is enough in tune with himself that he doesn’t try to overplay his power. His strength is less in the magic than it is in his tendency to stand at Point A, eye his goal at Point G, and strategise his way from one point to another. To his credit, when Tenar becomes caught up in his plan, he doesn’t throw her away after he uses her. He even treats her as the keeper of the Ring of Erreth-Akbe. Ged is going through his own heroic journey, which follows the usual trajectory—the hero descends into a sort of underworld, has an encounter with a powerful but restricted female figure, and emerges into the upper world with a boon—but Le Guin has shifted our attention to that female figure and in so doing has set the heroine’s constrained journey up against the hero’s freer one. The fact that neither Tenar nor Ged could win free without the other effectively collapses the binary. Tenar has to learn to act, and Ged has to learn to let someone else control his fate.

I’m not sure this book would be published today. It’s too easy to read Tenar as weak or see the first several chapters of the novel as static and dragging. I don’t think either is true, but the best aspects of The Tombs of Atuan are, like the Tombs themselves, buried deep. While I don’t envy Le Guin her 1969 brain or her (temporary) inability to imagine a woman as a Ged-like figure, I’m glad she wrote this book the way she did. Tenar is a wholly believable character, a teenage girl hedged about with rules and groping her way uncertainly towards the understanding that she is, despite appearances, allowed to make choices.

Next Up: I’ll introduce The Farthest Shore tomorrow and probably start reading it on the same day.

Bookmark Showcase: For this book, I went with a little metal harp bookmark I won from my harp teacher for practising for thirty days in a row (yes, I am motivated by stickers and small prizes).

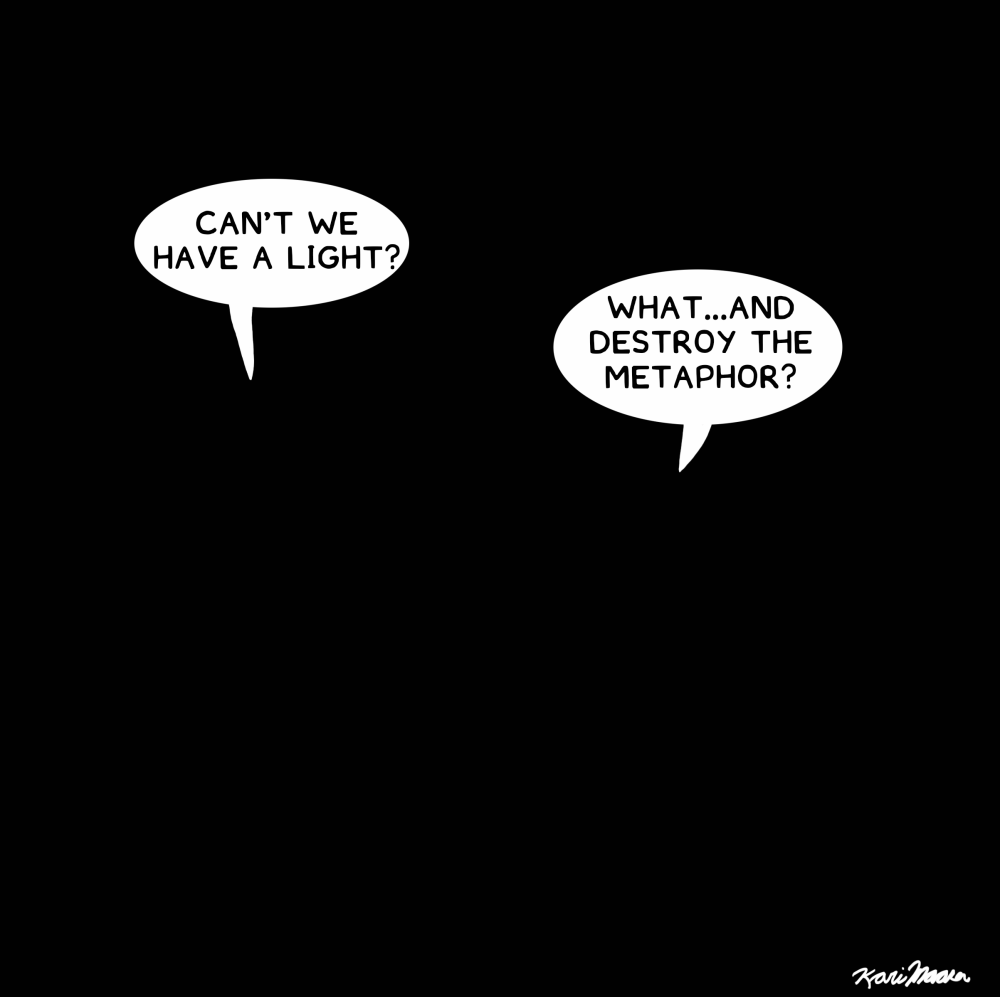

I loved those books when I read them – feels like decades ago. And your toon is perfect!

Heh…I’ve decided to do a little cartoon for each book. I wasn’t sure what to do for this one until I realised that OF COURSE it would take place entirely in the dark.